I’ve been a fan of WIRED for years, never a subscriber, but I’m always drawn to the print issue when perusing the magazines at my local bookstore or in an airport when bopping around the States (and sometimes the world). So I was excited to learn I would be reading “The Long Tail,” a New York Times bestseller, by WIRED editor-in-chief Chris Anderson, as one of my texts for a graduate class at Johns Hopkins.

The Wikipedia definition of “The Long Tail,” a business concept popularized by Anderson in a 2004 WIRED article, is riddled with terms like “probability distribution,” and “Gaussian distribution,” and words like “mean,” and “skewering,” so we won’t go all official here.

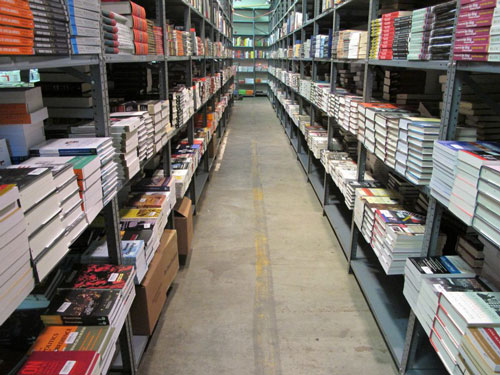

In layman’s terms, the concept is pretty simple to understand: brick-and-mortar stores, like, say, Barnes & Noble Booksellers, only have so much shelf space available to hold the “Twilight Saga,” “Fifty Shades of Grey,” Walter Isaacson’s 2011 biography of Steve Jobs, and other books that sell a large number of copies.

The in-store inventory makes up what percentage of all books ever produced? Less than one percent. However, book stores tend to carry the most popular books that will sell the most copies per week, month, quarter. But what about the other books that might only sell one copy in the same time period? Surely there is demand for all those books, right? This is the concept of “the long tail.” Business have realized that there is significant profits to be made by selling small amounts of a lot of things (almost exclusively online) to compliment the large amount of sales of a few items in brick-and-mortar locations.

Hundreds of thousands of books that will never see the shelf in a brick-and-mortar bookstore but you can buy them online and be reading in 24 hours. (photo: Harvard Online Bookstore Warehouse)

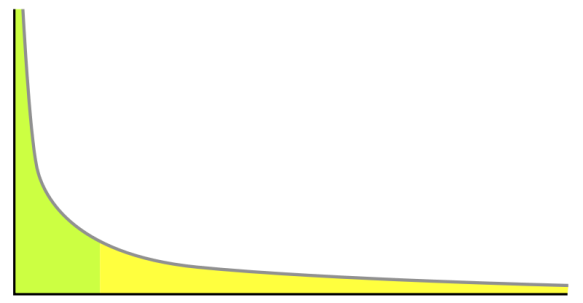

The graphic below is one often used to describe the theory visually. The far left, in green, represents the high-volume of sales of a small number of items. You see the long tail developing in the middle and to the right – this represents the large number of items that sell a smaller volume of units over time.

(A perfect real-world application of the theory: when I went to order books for my classes, there was one I was hoping to buy that day, which meant needing to visit my neighborhood B&N. When I stopped on my way home from work that evening I was told, “We don’t have that book in any of the local stores, but we can order it for you and have it delivered to you.”)

I had heard the term “the long tail,” but never took the time to learn the theory behind it, so I was glad to be reading Anderson’s book. I was really interested at the beginning, but I quickly grew tired of repetition – same theory, different company applying it.

I don’t want you to go leave this post with a sense that I did not enjoy the book, I did. In fact, from the beginning I was thinking about how a charity or fundraising organization might apply this theory and started thinking about my client for this semester, charity: water.

The long tail can, in a way, be applied to any organization trying to raise money to accomplish a goal. Follow me here: there is a limited number of places a organization can go to raise money. There is a smaller amount of incredibly wealthy people who, with a few strokes of the almighty pen, can underwrite a charity’s annual budget. On the flip side, there are a huge number of people of average wealth, who individually cannot donate huge amounts, but when combined together can make a huge impact.

The long tail graph above applies the exact same way in this case, and charity: water is a perfect example of this. It was almost as if founder and president Scott Harrison was reading this book when he threw a birthday party and started raising money for clean water wells back in the mid-2000s. What charity: water has been able to do is downplay the need for the large dollar donors and, instead applying the long tail method and putting power in the hands of the small-dollar donor, asking them to take ownership of a fundraising campaign, and take on the responsibility of making a difference. The organization’s fundraising arm, Mycharity: water, asks regular Joes to start campaigns, most of which raise a small amount of money.

I was trying to think of other organizations that do a great job of empowering their supporters to take the same level of ownership over a fundraising campaign that charity: water does and immediately one example came to mind. This organization, launched in 2007, relied on a huge number of small-dollar donations to make small contributions that when combined made a huge difference, eventually raising nearly one billion dollars. The man at the head of that organization is now the President of the United States.

(Full disclosure, I worked as a staffer on the Obama for America presidential campaign in 2008.)